What I learned from Erlang about Resiliency in Systems Design

Part of our daily business as developers, architects and operators is dealing with failure in computer systems. Even though you might be tempted to achieve 100% availability, this would be like trying to travel at the speed of light: just impossible. The effort, energy and resources you need to put into building such a system outweighs the benefits, ultimately leading to an unusable, i.e. too constrained, system.

That’s why we have to accept that fact that, like everything in life, nothing is perfect and will eventually fail.

“Expect the unexpected. Failures are a given and everything will eventually fail over time.”

This might sound obvious. But not too long ago, when I was in operations, I was taught that we should always use components with the highest mean time between failure (MTBF) rate. This is contrary to the current design principle to focus on mean time between recovery (MTTR), i.e. how quickly can you recover from failure. Took me a while to grok the essence of the latter, which in my opinion has several advantages compared to relying on MTBF:

- The higher the MTBF for a component, the more expensive it typically is; i.e. you can’t always afford the “best” component.

- A high MTBF, say 438.000 hours (50 years), doesn’t mean a lot in practice - it’s a theoretical (extrapolated) value based on certain conditions and testing by the manufacturer. Don’t blindly rely on it.

- Math and statistics will always beat1 you when you run at scale.

Knowing to think about failure states in software design, development and operations, the next question is how we deal with them, especially with the unknowns. There will always be failures that you have not planned for. And you could build the perfect machine, when we enter distributed systems (which essentially every real-world computer system is), we’re into the world of non-determinism. Welcome to reality! 🙂

“A distributed system is one in which the failure of a computer you didn’t even know existed can render your own computer unusable.”

(Leslie Lamport)

Fortunately, it’s a well explored field in computer science, and thus there’s already many great books2 3 4, courses5 and talks6 about how to deal with failures and improve the resiliency in (distributed) computer systems.

Instead of replicating that content in this post, I decided to elaborate on a pattern from the Erlang programming language which is so simple yet brilliant. In the end, I hope we embrace this pattern more often through the ever growing stack of layers and abstractions in the systems we build and maintain.

Wait, what do you mean by “Failure”?

I used the word failure many times in this post without actually defining it first. And it turns out I (we?) use related terminology like “fault” and “error” rather loosely and interchangeably in conversations. But the IEEE committee7 got us covered here:

(2) An incorrect step, process, or data definition in a computer program. This definition is used primarily by the fault tolerance discipline. In common usage, the terms “error” and “bug” are used to express this meaning.

In short, faults (e.g. caused by software bugs or hardware issues) put your system into an inconsistent state, eventually leading to failure. Thus, fault handling is imperative to maintain the correctness of your program and withstand failure for improved resiliency.

Let it crash!

Computer programs written in Erlang are known (and famous) for their robustness and tremendous uptime. To quote the creators of the language:

Once started, Erlang/OTP applications are expected to run forever (…).

An often cited example written in Erlang is the AXD301 with NINE nines reliability (99,9999999%). For the disbelievers: discussion on the math behind that claim here.

Apparently, the creators of the language found a way to trick the mighty failure gods. What have they done differently? Well, amongst many carefully evaluated design decisions that went into the language8, they came up with the philosophy of “Let it crash”. I.e., instead of writing a lot of defensive code to handle every possible corner case, you accept that there will be failures, where you separate the concerns and take corrective actions.

The separation of concerns in this case is based on the concept of a supervisor and supervision trees, where the supervisor deals with failure (crash) handling when faults in the business logic (worker processes in the tree) occur. Another advantage is that these processes don’t have to run on the same machine to benefit from the supervision concept. Furthermore, in Erlang, processes are isolated from each other and don’t share state. So you can further reduce the blast radius of failures on a process-level.

Often times, fault handling can be simplified by putting your system back into a known good (consistent) state. I.e. restart the failed process by a supervisor before it turns into a system-wide failure (outage). Perhaps a process thread run out of memory due to a large computation, a thread was blocked for too long with I/O starving the whole process, there was a rare corner case leading to a deadlock/ live-lock, a specific request was malformed, the process could not allocate additional file descriptors, etc.

Obviously there are failure scenarios where intentionally crashing and restarting just won’t fix the problem (bug). Please don’t read this as Michael’s free pass to write buggy software 😉.

Taking Erlang’s Philosophy to the Extreme

Why am I, as a Golang passionate, preaching the benefits of Erlang, you might wonder now? Well, due to the insanely fast growing tech entropy, i.e. every day a dozen of new tools, papers and programming languages, we tend to forget that often there exist simple battle-tested principles for the complex problems we need to solve.

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system.

To give you some examples from my daily work:

- You go crazy with error handling, try/catch et al. to make sure you captured all scenarios; whereas a simple crash (panic) and restart might do the job.

- You leverage a cluster architecture (or algorithm) for your system with crazy leader-election-paxos-black-belt-voodoo under the covers where a single instance with auto-restart perfectly covers your service level objective (SLO).

- You set up a super-duper monitoring system with tons of metrics and dashboards for your system to foresee (predict) a possible outage of your service; again, a simple restart, e.g. after you ran out of memory, could be totally within the SLO.

You see a pattern here: automatic restarts, aka “self-healing”, instead of complex error handling which Erlang revolutionized with the supervisor concept by the time it was created. Thinking about how to recover from a crash, i.e. MTTR over MTBF, right from the beginning of the design of your system without doubt increases resiliency. But the challenge has always been that there was no generalized implementation of the aforementioned supervisor for the majority of programming languages, operating systems and infrastructure (cloud) platforms out there.

Usually a mixture of shell scripting, OS process managers (systemd anyone?) and custom watchdogs was applied to model these self-healing capabilities. Not only is this error-prone and brittle in itself due to the many moving parts and let-me-script-that-for-you mentality (#LMSTFY 😂). It is also often implementation (application) specific and hard to standardize (abstract) to be applied across the board.

Containers to the Rescue

When container technology became mainstream, thanks to the Docker, Kubernetes and many other involved communities, a trend to standardize the design, packaging and execution of applications across infrastructure providers kicked in. One of the many advantages is a clear separation of concerns amongst the increasing number of abstraction layers, achieved by defining clean contracts (interfaces) between them or reuse of existing ones. E.g. Linux containers basically just being fancy operating system processes9.

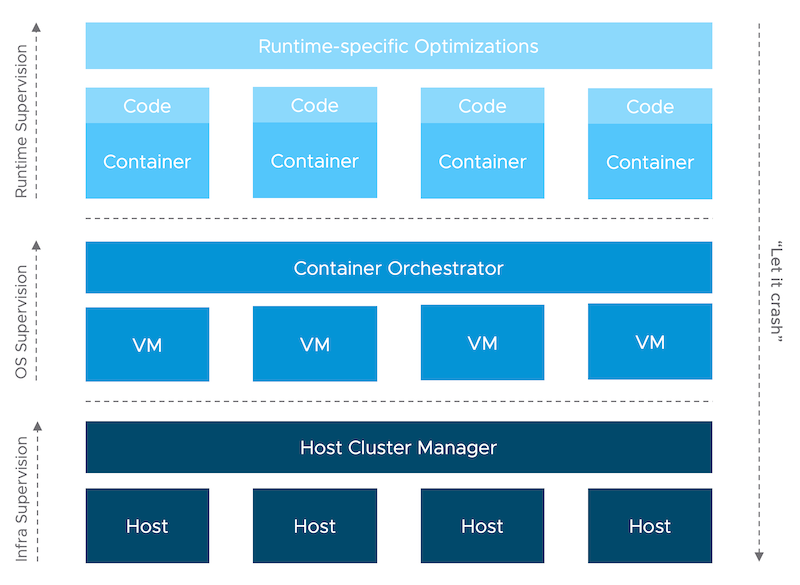

This is what we can use to our advantage to model an “end-to-end” supervisor throughout the whole stack, from infrastructure all the way up to your application. And the beauty of this is, again, the separation of concerns. There is no single “uber” supervisor, which would ultimately lead to the philosophical question “Who watches the watcher?”. Every layer, down to the physical hardware, implements the supervisor interface, to speak in software engineering lingo.

Example, please!

Ok, that was a mouthful. Let me run you through an example how this could look like from a 30k ft view. In fact, the idea for this blog post was sparked by the work with my awesome colleague William Lam. During some failure testing, he experienced hands-on the self-healing capabilities of a Kubernetes cluster after a forced VM shutdown (single node cluster). All the app containers (pods), incl. the Kubernetes control plane itself, magically came up after a reboot when the system had stabilized.

You might be like, yeah this is the reconciliation loop pattern with crash loop and exponential backoff logic 😎. For someone who’s new to Kubernetes, it’s a bit like magic to see how the whole cluster and applications come back up again. But what about the Kubernetes work horses, in this case kubelet and containerd?

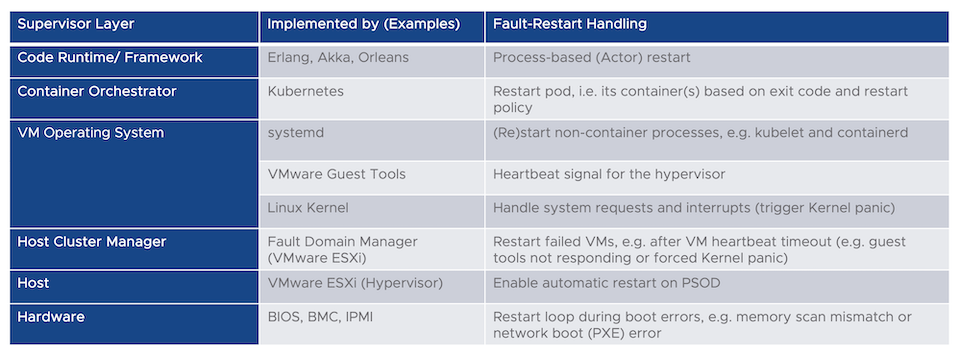

The following table describes a typical stack (first column) used to run applications these days. Now, every component (row) can be used to implement the supervisor interface, i.e. restart failed processes. I use the word process generically here. It could be an application, virtual machine, but also physical node (server/host).

At the top layer, obviously, there’s your code and runtime/ programming language specific behavior. Some modern runtimes (or frameworks), like Akka and Orleans (Microsoft), have builtin support for supervision, inspired by Erlang. Since it’s safe to assume that in the near future most of the applications will be packaged as an OCI-compatible artifact, we can make use of a container orchestrator for those runtimes and applications which don’t follow the Erlang supervisor concept. Kubernetes supports configurable restart behavior, e.g. if a container fails with exit code != 0 it will be automatically restarted by the orchestrator. There’s even the case for using both, say Akka and Kubernetes, together.

But some of the components of the orchestrator itself might not run as containers. Or perhaps your application cannot be containerized, yet. So how do we protect them? This is were the operating system comes into play. In many GNU/Linux distributions systemd is used to bootstrap and restart daemons, i.e. long-running background processes. Again, this is all configurable, e.g. restart delays, number of attempts, rate limiting etc.

Now we need to protect the operating system itself in case it crashes. Instead of complex clustering logic (who remembers the old Windows Server failover cluster days?), if your operating system is virtualized, defer the responsibility to the hypervisor. For example, in VMware vSphere, each guest runs a dedicated processes used to communicate with the hypervisor and signal heartbeats. If the hypervisor does not receive heartbeats or I/O activity within a certain interval (again, highly configurable), the VM is restarted and put back into a consistent state. I’ve seen customers leveraging this functionality by triggering a kernel panic and let vSphere recover the operating system. “Let it crash” taken to the extreme 🤓.

|

|

And the hypervisor? It’s a piece of software that can also fail. How can we protect that layer? Amongst many failure scenarios, the purple screen of death (PSOD) is a scary one in which the host determines a fault which it can’t handle. This is similar to a blue screen in Microsoft Windows or a Linux kernel panic (“oops”). Leaving aside the details on how vSphere would protect the VMs on that node, the host itself can initiate a restart instead of hanging in PSOD mode. Sounds a bit like magic, doesn’t it 😳?

Ok, so what about our lowest layer in the stack. The one that our complex software pyramid so much depends on? Hardware can and will fail, either due to a hardware component failure or external event, e.g. loss of power. But the good news is, that we also have some options here. Fundamentally, without some piece of low-level software (firmware), our hardware wouldn’t do much. It’s firmware like the BIOS or those in specific controllers, e.g. network and storage cards, which breathes life into the cold metal.

In the era of APIs and abstractions, most of you might not even notice that these firmware also implement crash-restart logic. For example, during boot the BIOS will scan the memory and restart if failures are detected. The same holds for disk and network controllers. If bootable devices can’t be found, e.g. during network (PXE) boot, the system will enter a restart loop (not technically a crash though), basically retrying forever. And in case of a power outage, after power has been restored, the BIOS can be configured to reset the system to the last known (or default) power status, i.e. powering on the system.

In conclusion, most of this might not sound new to you. But I wanted to remind us (incl. myself as always) that often there exists already a simple answer to a difficult question. Erlang’s concept of crash-restart supervision lives on in every abstraction layer. We just have to make use of it, instead of always reinventing the wheel. But that might be against the current Zeitgeist though 🙃.

Credits to Jonas Boner10, Bilgin Ibryam11 and Aaron Schlesinger12 for being a continuous source of inspiration!

-

The Network is Reliable: https://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=2655736 ↩︎

-

Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms: http://catalogue.pearsoned.co.uk/educator/product/Distributed-Systems-Pearson-New-International-Edition-PDF-eBook-Principles-and-Paradigms-2E/9781292038001.page ↩︎

-

Patterns for Fault Tolerant Software: https://books.google.de/books?id=jZgSAAAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&dq=resilient%20software%20pattern%20fault&hl=de&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false ↩︎

-

Secure and Resilient Software Development: https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/secure-and-resilient/9781439826973/ ↩︎

-

Distributed Systems (CPSC 416, Winter 2018): https://www.cs.ubc.ca/~bestchai/teaching/cs416_2017w2/index.html ↩︎

-

Patterns of resilience - the untold stories of robust software design by Uwe Friedrichsen: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9MPDmw6MNI ↩︎

-

IEEE Standard Glossary of Software Engineering Terminology: http://www.informatik.htw-dresden.de/~hauptman/SEI/IEEE_Standard_Glossary_of_Software_Engineering_Terminology%20.pdf ↩︎

-

Making reliable distributed systems in the presence of software errors: http://erlang.org/download/armstrong_thesis_2003.pdf ↩︎

-

What is a (Docker) Container, really? - https://speakerdeck.com/embano1/what-is-a-docker-container-really?slide=5 ↩︎

-

Without Resilience, Nothing Else Matters: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ktBlGj5gGUY ↩︎

-

It takes more than a Circuit Breaker to create a resilient application: http://www.ofbizian.com/2017/05/it-takes-more-than-circuit-breaker.html ↩︎

-

Kube Best Practices (Kubecon 2017): https://github.com/arschles/kube-best-practices ↩︎