QoS, "Node allocatable" and the Kubernetes Scheduler

What a title, sorry for that…Weeks ago, I started a post about a customer question which came up during a workshop. I just didn´t find the time to finish it, because of … other stuff. Also a BIG thanks to my Twitter fellows @bbrundert, @mhausenblas and @timoreimann for their review and feedback to improve this post. Make sure to follow them!

The Situation

The customer was wondering why the “Allocatable” resources (CPU, MEM) on the Kubelet would not be reduced when he starts “burstable” or “guaranteed” pods, i.e. pods with resource requests specified. As you are probably aware, “requests” are enforced by the scheduler/Kubelet during admission in order to guarantee the requested resource(s). Let’s use a short example (Minikube) to show what I’m talking about. All examples and code snippets are based on Kubernetes v1.7.8.

|

|

We see that the node reports an allocatable capacity of 4 CPUs and we launch 10 pods, each with 0.5 CPU requests to see what happens when we exceed capacity.

Hint: You can also query the node information via the API server under http://<API_SERVER>:8001/api/v1/nodes.

|

|

Apparently, the scheduler is doing its job and refuses to schedule all pods onto this node because this would exceed the node capacity and break the resource guarantee (QoS). However, and this is what confused the customer, the node still reports 4 CPUs as allocatable:

|

|

The Problem

How does the scheduler know that it should not put more pods onto this node if the node reports sufficient resources? This is what we’re going to answer in this post. Thanks to Kubernetes being open source, the code is the source of truth. Now, follow me into the rabbit hole of the Kubernetes scheduler…

The customer looked into to API documentation and was assuming that the

scheduler would use Allocatable during scheduling and admission. “NodeStatus

v1

core”

tells us that: “Allocatable represents the resources of a node that are

available for scheduling. Defaults to Capacity”.

But if Allocatable basically is a static field, where does the scheduler get the information about remaining capacity on the Kubelet? He could not find any other field in the API server (he even dug into etcd), so the customer’s theory was that the scheduler would track node.allocatable locally for each Kubelet and add/subtract resource requests as pods get scheduled/terminate. Since it’s the authoritative source of truth to make the binding of pods to a node (unless you run multiple schedulers, see note at the end of this post), doing the math would be easy, right? We’re getting closer…

But that would mean that the scheduler builds up local state. And as with many other components in the Kubernetes architecture, the (default) scheduler is supposed to be stateless, right? We should always assume it can crash (which it sometimes does, unfortunately). Building local state would mean, that the information about the actual allocated/remaining resources on the Kubelet is lost when the scheduler crashes/restarts. Eventually, we would break our QoS guarantee of sum(requests.cpu) < allocatable.cpu (or memory) because of missing information after a crash.

OK, but I can use leader election and run multiple instances of the default scheduler! Well, yes…no. Because there’s no replication going on between these scheduler instances, the customer was back at the beginning. He even simulated what would happen when he kills the default scheduler pod. He was surprised to see that the pending pods, before he killed the scheduler, remained in pending state. Again, due to insufficient cpu resources. The scheduler works correctly and somehow must recall memories from before it was killed…

The Solution

The Kubernetes engineers use a nice trick to reconcile state without having to track and persist all the resource information in a durable store, i.e. etcd. As you might be already aware of, Kubernetes controllers are event-driven and “level-triggered”, meaning that they set watches on the API server and get notified when objects are added/updated/deleted (see “A Deep Dive Into Kubernetes Controllers” for more information). Controllers persist this information in a local cache (Store) in order to reduce the load on the API server. When a controller starts, it registers watches (objects and events it’s interested in) with the API server and does a full sync on initialization. So it can start from a consistent state or reconcile state in case it crashed. If you’re interested in the details, stay with me…

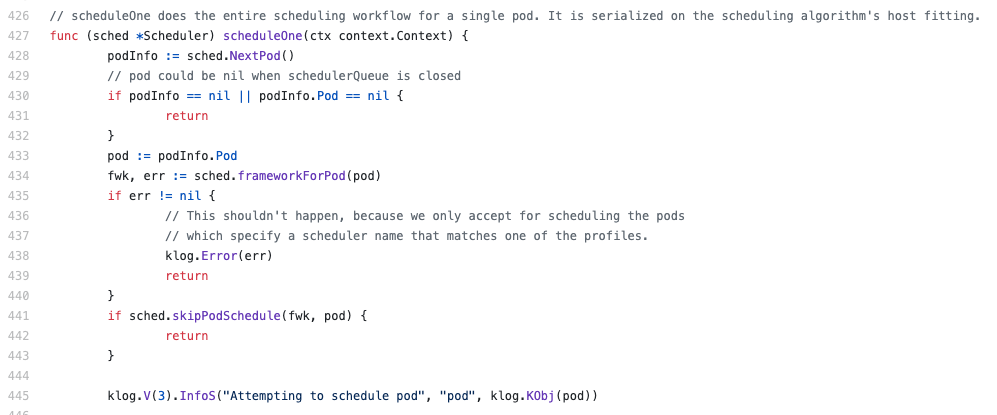

We start with the Run() function of the Scheduler struct. The scheduler remains in looping the scheduleOne() function until it shuts down/crashes. I reduced the code snippets to a minimum in order to ease reading. The main code lives inside plugin/pkg/scheduler/ and subfolders.

|

|

scheduleOne() pulls the next pod from an in-memory FIFO queue (within the scheduler) and calls a (blocking) function schedule(pod) to find a fitting node, based on “predicates” and “priorities”. It’s a two-step algorithm. First, nodes are filtered based on “predicates”, e.g. sufficient resources or certain labels. Second, the best node is selected, based on a scoring mechanism. You can read more about the process in “The Kubernetes Scheduler”.

|

|

The FIFO queue gets populated by EventHandlers in the NewConfigFactory(...) function.

|

|

Back to the scheduleOne() function above, sched.schedule(pod) handles (calls) the actual scheduling based on predicates and priorities.

|

|

generic_scheduler.go implements the algorithm.ScheduleAlgorithm interface (in the code snippet called via sched.config.Algorithm.Schedule). And here it gets even more interesting.

Both, UpdateNodeNameToInfoMap() and findNodesThatFit(), take a genericScheduler.cachedNodeInfoMap as an argument, which is of type map[string]*schedulercache.NodeInfo.

|

|

What is NodeInfo about? It is the scheduler’s view of each node. The NodeInfo struct reveals the following:

|

|

For each node, requestedResource is where the scheduler caches the information about how many resources have been requested (are guaranteed), taking into account the node exposed allocatableResource mentioned in the beginning of this post. So the final question is, how does requestedResource get initially populated, e.g. after a crash? Because this is what should be done in order to feed the scheduling algorithm with correct information about the resource capacity of the Kubelet (NodeInfo). We’re back at the NewConfigFactory(...) function we have already seen. This time we look at the EventHandlers which use a FilterFunc “assignedNonTerminatedPod”. From the function documentation:

|

|

Basically, this function looks for running pods in the cluster. The ResourceEventHandlerFuncs in NewConfigFactory(...) update the scheduler cache based on this information.

|

|

All Add/Update/Delete EventHandlerFuncs call into their related cache functions. As an example:

|

|

This calls into the corresponding function in schedulerCache which calls an unexported function addPod(pod *v1.Pod). This function calls n.AddPod(pod) to update the node information based on a NodeInfo struct.

|

|

And finally, we can see where requestedResource, the actual consumed (requested) resources on the node (Kubelet), gets populated.

State reconciliation: done :)

|

|

Long story short: reconciliation of the scheduler state, so to say, is based on setting watches on the API server. During startup these watch functions trigger, the scheduler cache gets populated with the current node state (capacity/requested resources) and uses this information to correctly schedule any pending pods.

You might wonder, what if there’s something wrong with the cache or events are missed? We’re living in a distributed system and there is always the likelihood of inconsistencies. Fortunately, the Kubelet is the last mile and does “final” admission, based on predicates (e.g. remaining node capacity). So even if the scheduler would make a wrong binding, QoS enforcement is guaranteed by the Kubelet.

A final note on running multiple schedulers

Running multiple distinct schedulers in Kubernetes is another proof of the extensibility Kubernetes offers - by design. But those schedulers do not share requestedResource metrics. This results in an optimistically shared state scheduling environment, where conflicts need to be detected and resolved. Xiaoning Ding (Huawei) did a great presentation on this topic last year at KubeCon Seattle: “Running Multiple Schedulers in Kubernetes”. If you’re interested in this topic, make sure to watch the talk.

Alright, you’re still here! Thank you for reading this article. If you found any inconsistencies, “bugs” or if I was not clear enough, ping me on Twitter and let me know.

As always, feel free to share and spread the word!